An optimality proof of the Muon weight update

2025-07-19

Using basic linear algebra to prove that "orthogonalizing" the gradient gives the optimal loss improvement under a norm constraint.

This article expects comfort with undergraduate linear algebra. It aims to be explicit and self-contained, with proofs of useful lemmas included in the appendix.

In Jeremy Bernstein’s great post Deriving Muon, he motivates the weight update for the Muon optimizer using a constrained optimization problem. He gives the solution for the optimal weight update, but I wasn’t sure how he arrived at it.

In this post, I provide an optimality proof of the solution. If you’re already familiar with Muon and the constrained optimization problem used to derive its weight update, click here to jump to the proof.

Addendum 2025-07-28: Laker Newhouse pointed out that he and Jeremy also provide a proof of this result in a Dec 2024 paper. See Proposition 5 and its proof in Appendix B. Thanks Laker!

A quick recap of Muon

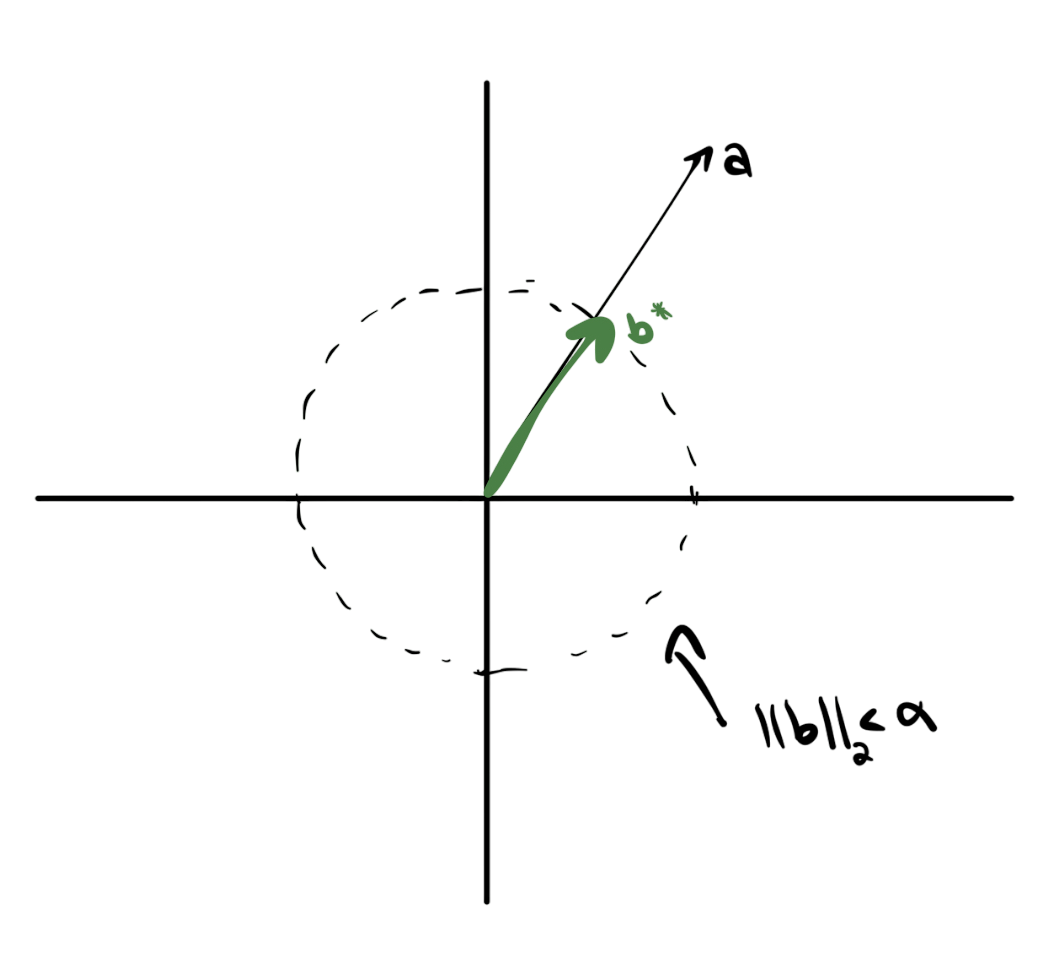

Define a loss function . Consider it as a function of the weights of one linear layer, . For a given change in the weights , the new loss value at is approximately using the first-order Taylor approximation. Here, the inner product is the Frobenius inner product on matrices,Using this Taylor approximation, the change in loss is therefore roughly the inner product Muon aims to maximize the improvement in loss, subject to a norm constraint on .

Specifically, it employs the root-mean-square operator norm, We’ll properly derive this norm below. But briefly, is the largest possible factor by which a matrix can scale the size of its input, normalized by dimension: So we arrive at the constrained optimization problem () that motivated Muon: For intuition, the requirement that is equivalent to the condition that the change in the layer’s outputs is bounded by the size of its inputs. From (), for all . So the constraint directly ensures that the layer’s outputs don’t change too much within an optimization step.

If we take the singular value decomposition of the gradient as , then the solution to is given as the “orthogonalization,” In this post, we’ll derive this solution and prove that it is optimal for (). First, some background on the RMS operator norm.

Preliminaries: RMS norm

For an -dimensional vector , the RMS norm is defined as A useful fact for intuition is that the RMS norm is just the norm, rescaled such that the ones vector has norm instead of : This rescaling allows for a “dimension-invariant” notion of size.

We can use this vector norm to define a norm on matrices.

Preliminaries: RMS operator norm

The RMS operator norm is defined to be the largest multiple that a matrix can increase the RMS norm of its input: This is trivially equivalent to the definition from . Expanding the RMS operator norm using the RMS vector norm definition, The RMS operator norm can also be expressed in terms of the singular values of . For those familiar, the right-hand supremum in the equation above is known as the spectral norm, The spectral norm of a matrix, the most can stretch a vector in the sense, is precisely its largest singular value: See Fact 1 for a formal proof. Taking the equality at face value, we now observe, We now have all the machinery we need to solve the Muon problem (). Before we do so, let’s warm up with a simpler problem.

Warmup: Maximizing inner products

Consider the linear program,

The answer is likely immediately obvious: pick in the direction of , scaled to the appropriate norm size. Specifically, let be

Picking to be “aligned with” to maximize the inner product is pretty intuitive. But how might we prove this?

Picking to be “aligned with” to maximize the inner product is pretty intuitive. But how might we prove this?

One option is to assume that we’ve found a better candidate, say , and find a logical contradiction. If we find a contradiction, the better candidate cannot actually exist—so we win.

Proof: let’s assume that we have such that We want to show that any such is not a valid solution to our linear program. To do so, we’ll show that it violates the norm condition, meaning

We’ll do this using the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality1. The inequality tells us that Using our assumption that , So doesn’t satisfy the norm constraint, meaning it is not a valid solution to the problem.

But the only thing we asked of is that it has a better objective value than . Therefore the same argument applies to all vectors with . This means that all vectors with a strictly larger objective value are invalid solutions. In other words, is optimal.

End proof.

With this, we’re now equipped to analyze the Muon problem.

Back to Muon

The parallels between the warmup problem, and the Muon problem (), should be clear. In both cases, we’re optimizing an inner product over a norm ball.

For ease of exposition, we’ll frame the Muon problem () as a maximization problem in this article. So we’ll instead aim to solve: To build intuition for the solution , we’ll first solve a slightly simplified version of the problem in which will arise naturally.

Then, like the warmup, we’ll proceed by contradiction and show that any candidate better than does not satisfy the RMS condition.

Why orthogonalize? Deriving a solution a priori

First, the simplified problem.

Based on the warmup, to optimize our inner product objective, we might expect a solution that feels like a matrix “in the direction” of . So let’s restrict our attention to matrices with the same singular basis as .

This simplification will allow us to analytically derive the optimal weight update .

Reducing to the same singular basis

Since , a valid SVD of the negative gradient is simply So take to be a matrix for some arbitrary nonnegative diagonal matrix .

Writing out the objective value, we have It turns out that the Frobenius inner product does not change when you pre- or post-multiply by orthogonal matrices (Fact 2). So Since is a diagonal matrix, we can write the matrix inner product as a function only of the diagonal entries of each matrix: We can simplify this expression even further. If we pull out the diagonal elements into vectors, defining and , we can rewrite the sum as We’ve now reduced the matrix inner product objective to a vector inner product.

We can also express the norm of in terms of . Since the entries of are the singular values of by construction, we have that by equation .

In our restricted setting, then, we’ve now successfully reduced the matrix-domain problem () to the vector-domain problem, This reduced version is quite easy to solve.

Deriving a solution

Since represents the singular values of , it must have nonnegative elements. So maximizing the inner product is equivalent to maximizing each of the component products .

Under our constraint on , then, the best solution to this reduced problem is simply the constant vector

If this isn’t immediately obvious, try to prove it yourself.

Translating from the vector parameter to the matrix parameter , the best solution to our restricted matrix-domain problem is therefore This is precisely the optimal value () given by Bernstein!

It’s now clearer why it’s a good idea to define our weight update as the negative gradient with its singular values “clamped” to .

For a weight update in the same singular basis as , the inner product objective and the RMS norm are expressible entirely in terms of the singular values of and . The inner product objective turns into a dot product between two nonnegative singular value vectors . And the RMS norm constraint turns into an element-wise maximum constraint on the singular values of . The optimal solution is therefore just to clamp the parameters to their maximum allowable values.

Just like the warmup problem, then, the solution is a “rescaled” (singular value clamped) matrix “in the direction of” (in the same singular basis as) the negative gradient .

With this intuition, we can dive into the proof.

A proof of optimality

The proof is not as elegant as the warmup, since we can’t use Cauchy-Schwarz.2 But it relies on the same contradiction technique.

Assume we have some matrix that does better than , meaning We’ll show that and therefore that cannot be a solution to .

Proof: First, we’ll rewrite in terms of the singular basis as defining . With this, we can simplify the problem expression slightly.

Using the fact that the Frobenius inner product is invariant under orthogonal transformations of its inputs (Fact 2), we can rewrite the objective as: Since is diagonal, this reduces to Applying the same argument to , we have Our assumption in means that So For this sum to be strictly positive, at least one term must be strictly positive. Call this term . All singular values are nonnegative, so . For the th term in the sum to be positive, then, we must have This fact will be the key to showing .

By Fact 3, the RMS norm is invariant under orthogonal transformations, so It therefore suffices to show To do this, all we need to do is find one vector such that Pick to be the th coordinate vector, meaning Note that has unit norm, so So is just the th column of , meaning In particular, Now, we can calculate and attempt to show (). since all other terms in the sum are nonnegative: . But from equation , we therefore have that Applying this inequality to the RMS norm, we find Therefore . So cannot be a valid solution to the problem, and as given in Equation () is optimal.

End proof.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored and proved the optimality of the solution to the Muon constrained optimization problem (). We situated it within the framework of maximizing an inner product over a norm ball, and used this analogy to motivate the otherwise potentially-unintuitive formula.

Appendix: Useful Facts

Fact 1

The spectral norm of a matrix is its largest singular value.

For any matrix , where is the largest singular value of .

Proof: Let be the SVD of . Without loss of generality, assume the singular values are ordered in descending magnitude, so .

To prove the equality, it suffices to prove the inequalities We’ll start with the left hand inequality.

Step 1: Maximum Singular Value Spectral Norm

To show this, it suffices to find some vector such that But this is trivial. Let , where is the coordinate vector with first component and all other components . Then Taking norms, I claim that , where the middle equality follows because orthogonal matrices preserve norms. The proof of this claim is simple. Let be an orthogonal transformation and an arbitrary vector. Then And so . Therefore, we’ve found a vector such that So the spectral norm must be at least the maximum singular value,

Step 2: Spectral Norm Maximum Singular Value

For this inequality, we need to show that for all vectors .

Again relying on the fact that orthogonal matrices preserve the norm, Therefore = . Define , so

Each element of is just . And each diagonal element is bounded by the maximum singular value, . So And therefore But and is orthogonal, so . We conclude, End proof.

Fact 2

The Frobenius inner product is invariant under orthogonal transformations.

Let and be arbitrary matrices. And let be orthogonal matrices, meaning Then Proof: Expand out the definition of the Frobenius inner product, Using the cyclic trace property3, this reduces to End proof.

Fact 3

The RMS norm is invariant under orthogonal transformations.

Let be an matrix, and let be orthogonal. Then Proof: For brevity, call . Since it suffices to show that and have the same singular values.

Say is the SVD of . Without loss of generality, order the singular values in descending magnitude, so So we can write as But since are all orthogonal matrices, the above is a SVD of . So the two matrices have the same maximum singular value, Therefore End proof.

-

In short, the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality states that for any two vectors , the magnitude of their inner product is at most the product of their norms:If you haven’t seen it before, it’s worth trying to prove. Here’s a sketch: restrict your focus to the case where both and have unit norm: . Assume you have some pair with . Then what must be true about ? ↩

-

Cauchy-Schwarz type inequalities only hold for norms induced by inner products. Specifically, say is a vector space equipped with an inner product . This inner product defines a norm on as well, given by Using this norm, we have a Cauchy-Schwarz inequality:These inequalities do not necessarily hold for other norms. For example, consider the vector given by . And consider the norm, . The Cauchy-Schwarz inequality does not hold for the pairing between the standard inner product and the norm:In the Muon setting, we cannot use Cauchy-Schwarz because the Frobenius inner product does not induce the RMS norm: ↩

-

The cyclic trace property states thatIt is quite easy to prove, and worth doing as an exercise. Start by showing that the trace is commutative, meaning ↩